Former intern helps launch GGBA high school program

This spring, Golden Gate Bird Alliance partnered with the East Oakland Boxing Association to offer a pilot eight-week high school environmental program. EOBA is a 25-year-old youth leadership organization located on 98th Avenue, just a few miles from Arrowhead Marsh. Besides offering athletic training, EOBA hosts after-school tutoring, an organic garden internship, classes in dancing, cooking, and more. GGBA was able to offer EOBA a field-trip based environmental program, introducing ten high school students to the natural areas of the Bay through weekly trips to local parks. Activities included birding, bug identification, native plant restoration, and a tour of a wildlife rehabilitation center. The partnership with EOBA was a way to expand our previous high school internship program to serve a larger number of teens.

Martin Rochin, a former high school intern with Golden Gate Bird Alliance, was able to return to work with us as a college intern for the program with EOBA. Below he reflects on his experience as mentor to the high school students.

—————————

By Martin Rochin

I first began working with Golden Gate Bird Alliance in 2007, when I was only 16 years old. As a child in a low-income family in East Oakland, I hadn’t really explored the natural world around me. I seldom strayed from my bus route to school.

When my teacher at Oakland Unity High School told me about the internship opportunity at Golden Gate Bird Alliance, the idea of being outdoors, identifying birds, and doing restoration work was foreign to me. Through the internship, I was able to visit places such as Arrowhead Marsh and Alcatraz – places that I had been surrounded by all along, but was completely unfamiliar with.

This was what I had in mind when Marissa Ortega-Welch offered me an opportunity to come back and work with GGBA as an assistant in the first-ever environmental high school program at the East Oakland Boxing Association. Six years after my high school internship experience with GGBA, I had completed two years of college at U.C. Santa Barbara. I was back in Oakland, working to raise money to complete college. I had reached out to Marissa and Anthony DeCicco at GGBA simply in the hopes of finding a job that would be more enriching than working in retail.

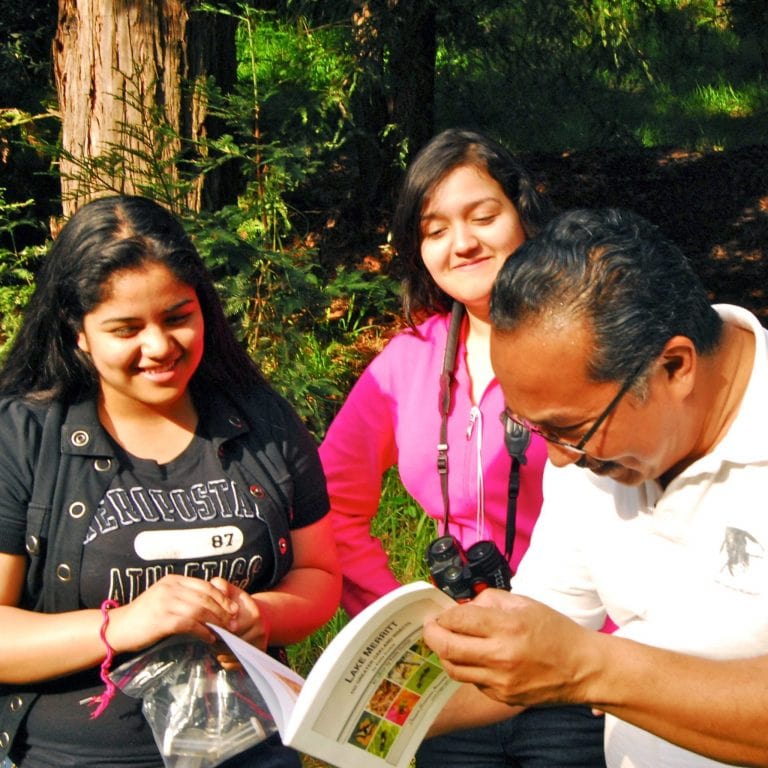

Martin Rochin (far right) as a high school student, on a trip to Yosemite with the GGBA high school internship program in 2007.…

Martin Rochin (far right) as a high school student, on a trip to Yosemite with the GGBA high school internship program in 2007.…