Audubon — the man and the meaning

By Ilana DeBare

Who was John James Audubon? Why was the leading U.S. bird conservation organization named after him? Has his meaning as a figurehead changed?

The National Audubon Society board of directors announced this month that, after a year of deliberation, it will not replace the “Audubon” part of its name. But the name debate continues: NAS staff issued a sharp denunciation of the board’s decision, three NAS board members resigned in protest, and a number of chapters such as Seattle, Portland, and Madison are still moving ahead with plans to change their own names.

As the Golden Gate Bird Alliance board deliberates over our own response, it’s a good time to review what we know about John James Audubon—both the man and his meaning.

John James Audubon was a complex character who was known to make up stories about himself. Sometimes it’s hard to know what’s fact and what’s self-serving myth. In addition, the lens through which many of us look at Audubon and his personal history has shifted over the past decade.

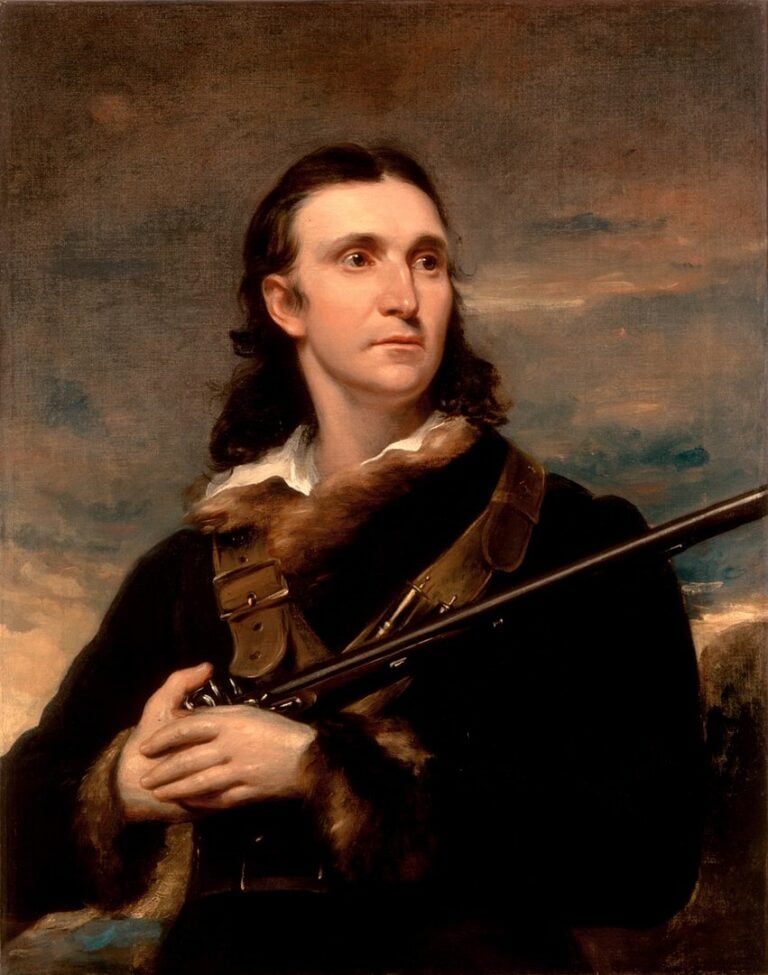

Portrait of John James Audubon, 1826, by John Syme. White House collection.

Portrait of John James Audubon, 1826, by John Syme. White House collection.

The man

Let’s start with one of the most basic facts about someone—their birth. It’s undisputed that John James Audubon was born out of wedlock in 1785 to a French naval officer on the island that now is Haiti. But his mother? Most historians say she was a white French chambermaid who died shortly after childbirth, although a few sources claim she was an enslaved person of color. Audubon himself made up a third and entirely false story, claiming at one point that she was a “lady of Spanish extraction” from Louisiana who was killed in a slave uprising.

Some conservationists have promoted the theory of Audubon having Black ancestry as a way to welcome people of color into the birding community. More recently, the question of his ancestry has been overshadowed by his history as a slave owner and his statements in support of enslavement.

Audubon’s father raised him in France and sent him to Pennsylvania at age 18 to prevent his conscription into the Napoleonic wars. After marrying, he moved to Kentucky, which at the time was part of the country’s western frontier. He started a series of business ventures and failed at just as many. (At one point he went bankrupt and was jailed for debt.)

Audubon was an expert woodsman—good at shooting, orienteering, and swimming.…

Derek Heins, the team captain of the East Bay Scrub Jays competing in the Bay Birding Challenge this year – photo provided by Derek Heins

Derek Heins, the team captain of the East Bay Scrub Jays competing in the Bay Birding Challenge this year – photo provided by Derek Heins

Caitlyn Schuchhardt birding – Photo provided by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

Caitlyn Schuchhardt birding – Photo provided by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

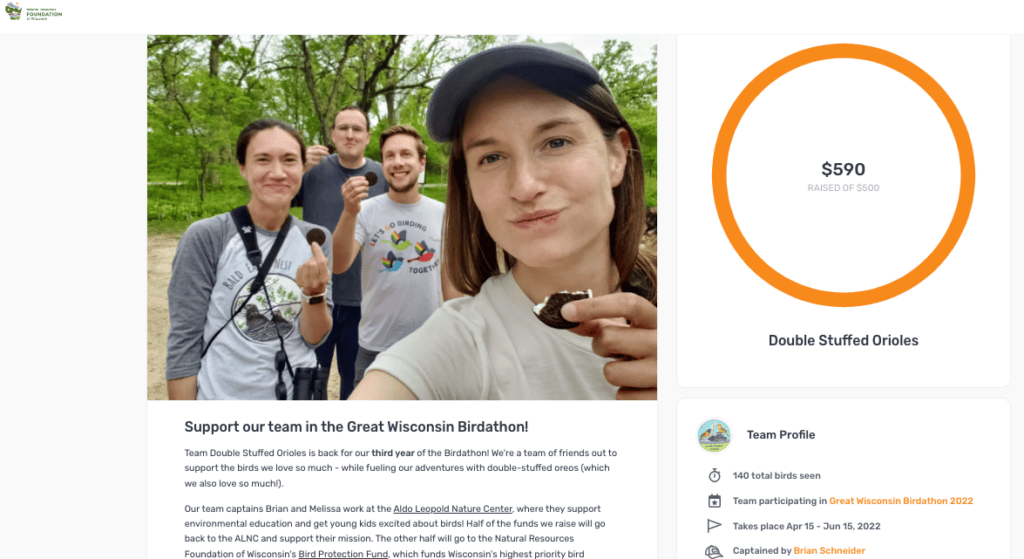

Orioles Fundraising Page Screen shot – Provided by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

Orioles Fundraising Page Screen shot – Provided by Caitlyn Schuchhardt

Temporary logo Seattle chapter is using during its name changing process.

Temporary logo Seattle chapter is using during its name changing process.