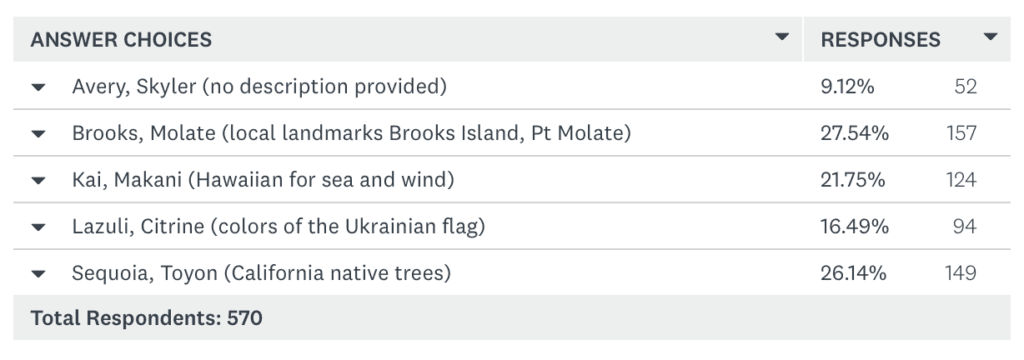

How to See Nesting California Least Terns and their Chicks

By Marjorie Powell

California Least Terns (Sternula antillarum browni) can be seen plunge-diving for fish at several East Bay locations in the summer but seeing them nesting is more difficult. Traditionally, Least Terns make scrapes in the sand to lay their two or three eggs, but with beaches full of people and dogs, the terns have found other nest sites. At the Alameda Wildlife Reserve and Hayward Regional Shoreline, large fenced areas protect nesting terns in the Bay Area from mammal predators (feral cats, racoons, etc.) and human disturbance. Devoted birders can serve as monitors for the nesting colonies, alerting US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) when an aerial predator appears (Peregrine Falcons are especially skilled at taking eggs, chicks and sometimes adults), but training for new monitors at the Alameda Reserve has not happened since the start of COVID, and monitoring provides no option for other birders or potential birders.

People board a bus for the trip to the Least Tern colony at Alameda Wildlife Reserve on June 25, 2022 by Rick Lewis

People board a bus for the trip to the Least Tern colony at Alameda Wildlife Reserve on June 25, 2022 by Rick Lewis

About the only other option to see eggs and chicks is Return of the Terns. A cooperative endeavor between USFWS, which manages the colony at the Alameda Wildlife Reserve for the Department of Veterans Affair, which now holds title to the land, and Crab Cove, part of the East Bay Regional Park District, Return of the Terns is a yearly event where members of the public can learn about the endangered species. Pre-registered participants spend around 30 minutes on a school bus inside the reserve’s outer fence looking over the breeding site fence to watch chicks running and adults holding small fish while searching for their chick. An unadvertised bonus is the view of San Francisco from the northwestern corner of Alameda.

San Francisco is impressive even in the haze when seen from the northwest corner of the Reserve in Alameda by Rick Lewis

San Francisco is impressive even in the haze when seen from the northwest corner of the Reserve in Alameda by Rick Lewis

This year’s presentation was outdoors, with pictures projected onto a canopied screen. Susan Euing, the USFWS Wildlife Biologist who manages the colony, gave the first presentation about Least Terns’ life cycles and nesting practices and then lead three bus tours of twenty-five people to the colony. A Crab Cove naturalist gave the latter two presentations while tours were happening. One important take-away from the presentations is that nesting success depends on the presence of small fish and the absence, or at least lesser presence, of a Peregrine Falcon (they also nest in Alameda).…

Beaver Dam by Elizabeth Winstead

Beaver Dam by Elizabeth Winstead

Beaver Lodge and Great Egret

Beaver Lodge and Great Egret

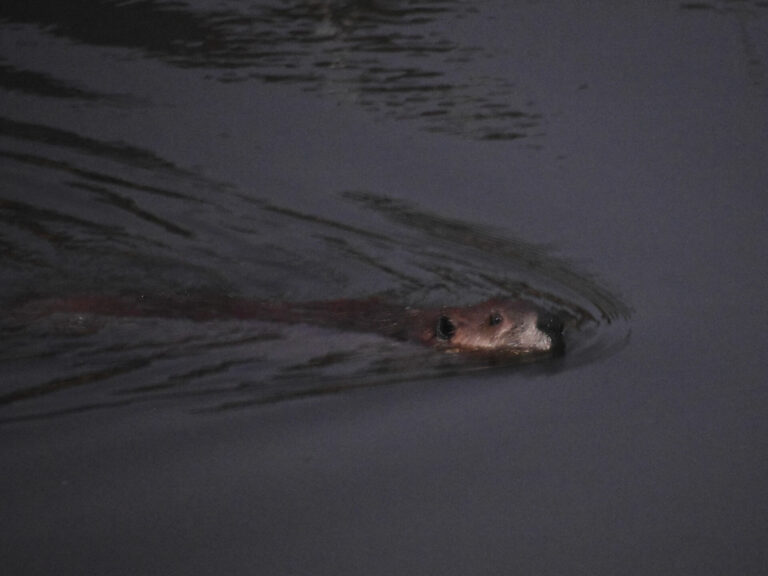

Beaver at dam

Beaver at dam

Female Red-winged Blackbird

Female Red-winged Blackbird

Photo of chocolate tasting provided by Cacao Case

Photo of chocolate tasting provided by Cacao Case