The Vanishing Chorus: A Reflection on North American Birds in Decline

by Kenneth Hillan

Wilson’s Warbler, Roys Redwoods Preserve, Spring 2025 – Kenneth Hillan

Wilson’s Warbler, Roys Redwoods Preserve, Spring 2025 – Kenneth HillanIn the bustling and growing town of Paisley, Scotland—the place of my birth—a young Alexander Wilson once wandered the woodlands, unaware that his journey would lead him across the ocean to North America. From his letters home, what he encountered in the New World was beyond anything he had known or imagined: skies teeming with birds, forests alive with song, rivers echoing with nature’s pulse. Two centuries later, I reflect on Wilson’s experience—and the troubling question: what remains of that magnificent abundance today?

On May 1, 2025, a landmark study, published in Science, revealed a sobering truth1. Of 495 North American breeding bird species, fully three-quarters have declined significantly in some part of their range over the past 15 years. The research, led by Alison Johnston and a team at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, is based on an analysis of nearly 37 million eBird checklists submitted by observers between 2007-2021. The conclusions from the research, grounded in rigorous data analysis combined with national as well as local habitats, paint a portrait of a continent in quiet crisis. A summary of key findings and takeaways from their publication can be found in a one page summary here.

Curiously, the decline is not always where one might expect. Some species appear to thrive in fragmented habitats—perhaps a mall here, a restored marsh there—offering the illusion of recovery. But these modest gains, while welcome, are dwarfed by losses in the vast habitats where these birds are most common, as populations are declining most severely where they are abundant.

What sets this study apart is its use of fine-scale trend mapping—measuring bird population change in grids of approximately 10 square miles, rather than just looking across broad regions. This higher resolution has revealed a more nuanced picture: while most species are declining, many also show areas of local increase. For conservation groups like GGBA, this represents a powerful shift. It allows us not only to target urgent declines but also to identify and build upon local successes—guiding action where it can be most effective.

In the San Francisco Bay Area and the Central Valley, the study data highlights significant declines in wetland and coastal breeding birds, mirrored by parallel losses in the wintering populations of local species that breed in the North American Arctic.

Here in California, birds that depend on wetlands for breeding have been among the hardest hit.…

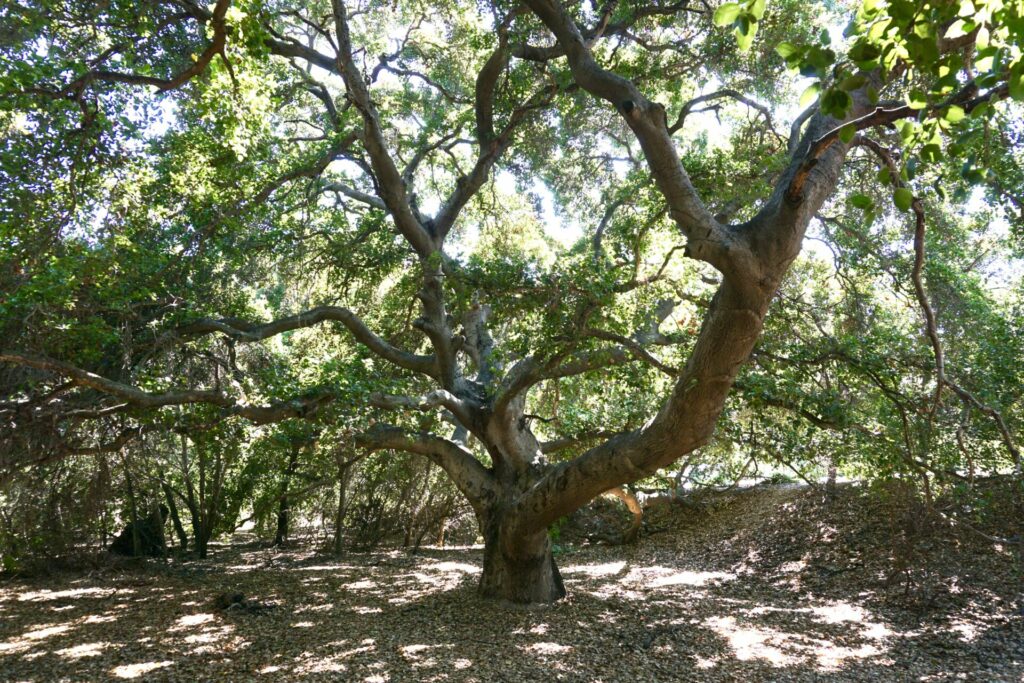

Coast Live Oak /

Coast Live Oak /

Cypress Grove, Marshall CA / provided by Nils Warnock

Cypress Grove, Marshall CA / provided by Nils Warnock

Nils and David Lumpkin banding a short-billed dowitcher at the Walker Creek Delta in Tomales Bay / S. Jennings)

Nils and David Lumpkin banding a short-billed dowitcher at the Walker Creek Delta in Tomales Bay / S. Jennings)