The Journeys of Debi Shearwater

An interview with Debi Shearwater, founder of Shearwater Journeys and recipient of the Ludlow Griscom Award at the 2018 Monterey Birding Festival

By Taylor Crisologo

Debi Shearwater received the Ludlow Griscom Award at the 2018 Monterey Birding Festival held in Monterey, California. The award is given by the American Birding Association to an individual who has made significant contributions to our understanding of a region’s birds.

Debi Shearwater, famous for her incredible knowledge of seabirds, is the founder of Shearwater Journeys, Inc. Shearwater Journeys offers birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts the opportunity to venture out from California’s central coast to see seabirds and other marine life.

Mark Rauzon, Seabird Biologist, noted author, and Professor of Geography, offered this about Debi Shearwater, “Debi is a true visionary- a self made legend of the birding community, famously portrayed by Anjelica Huston in the movie The Big Year. She was a pioneer of sea birding on the West Coast, developed a business, Shearwater Journeys, and carried it on for 43 years. Since 1976 more than 67,000 birders from every state in the USA and more than 30 countries worldwide have had an opportunity to appreciate seabirds and the phenomena of Monterey Bay oceanography. One of the first women birders to achieve national recognition, she has many firsts, including discovering new North American species like the Jouanin’s Petrel.”

Debi came to California in 1976. “I thought I was only going to be here for about 18 months,” she exclaimed. Within 10 days of arriving in the Golden State, she arranged to go on her first pelagic trip from Monterey. After a great experience, she booked another Monterey trip for that September – just six months later.

“In those days, there were no field guides to whales. They didn’t exist. There were really no good field guides to seabirds at that time either,” Debi explained. She spent the night before reading books about blue whales – an IUCN Red List endangered species whose global population was driven to drastically low numbers by commercial whaling. “I just thought, man, if I see a whale – that’s going to be amazing.”

Blue Whale tail by Beth Hamel

Blue Whale tail by Beth Hamel

On her trip in September, Debi encountered a blue whale: the first whale species she’d ever seen. The following year, she spotted a Streaked Shearwater – a rare sight in California, since its native range is the western Pacific Ocean. “That’s how it began – with a blue whale and a Streaked Shearwater,” she said.…

Photo of campers starting a birding project by Emily Zugnoni

Photo of campers starting a birding project by Emily Zugnoni

Campers making bird whirligigs by Emily Zugnoni

Campers making bird whirligigs by Emily Zugnoni

First Light by Deborah Jacques

First Light by Deborah Jacques

All 4 BRPE Band Programs represented at Alameda Breakwater Band Collage by Deborah Jaques

All 4 BRPE Band Programs represented at Alameda Breakwater Band Collage by Deborah Jaques

Leora counting from shore by Deborah Jacques

Leora counting from shore by Deborah Jacques

A Great Egret, a majestic white bird with a five-foot wingspan, takes to the air. One might imagine that this elegant large creature inhabits only exotic settings, but in fact this egret lives at the heart of the extremely urban San Francisco Bay Area. This bird belongs to an egret colony on Bay Farm Island off the southern tip of Alameda.

A Great Egret, a majestic white bird with a five-foot wingspan, takes to the air. One might imagine that this elegant large creature inhabits only exotic settings, but in fact this egret lives at the heart of the extremely urban San Francisco Bay Area. This bird belongs to an egret colony on Bay Farm Island off the southern tip of Alameda.

A Monterey pine leans over the lagoon on Bay Farm Island in Alameda, home to a San Francisco Bay Area egret breeding colony. Nesting begins as early as February and continues through August. The egrets and the tree are almost hidden. After the chicks are born and they begin to grow, the tree will resound with the rhythmic clacking of egrets.

A Monterey pine leans over the lagoon on Bay Farm Island in Alameda, home to a San Francisco Bay Area egret breeding colony. Nesting begins as early as February and continues through August. The egrets and the tree are almost hidden. After the chicks are born and they begin to grow, the tree will resound with the rhythmic clacking of egrets.

Due in large part to Golden Gate Bird Alliance, the removal of a dying tree is postponed until after the egrets’ breeding season.

Due in large part to Golden Gate Bird Alliance, the removal of a dying tree is postponed until after the egrets’ breeding season.

In March 2018, ten Great Egrets arrive. Soon they are joined by another four. Two weeks later, a pair of Snowy Egrets arrive.

In March 2018, ten Great Egrets arrive. Soon they are joined by another four. Two weeks later, a pair of Snowy Egrets arrive.

A Great Egret brings a gift of a branch to woo his mate and repair their nest.

A Great Egret brings a gift of a branch to woo his mate and repair their nest.

And then there are chicks!

And then there are chicks!

It is feeding time for the chicks. The parent’s bill and most of the head are inserted into the chick’s mouth and down the throat.

It is feeding time for the chicks. The parent’s bill and most of the head are inserted into the chick’s mouth and down the throat.

Chicks build biting strength and coordination, as they nip the parent’s beak.

Chicks build biting strength and coordination, as they nip the parent’s beak.

Fledgling egrets, now as large as their parents, experience quick changes between harmony and raucous battles in the nest. They are stretching their wings and learning to fly.

Fledgling egrets, now as large as their parents, experience quick changes between harmony and raucous battles in the nest. They are stretching their wings and learning to fly.

New egret life abounds in the dying tree. By summer the pine’s green needles have disappeared leaving a clear view of the abundant breeding season.

New egret life abounds in the dying tree. By summer the pine’s green needles have disappeared leaving a clear view of the abundant breeding season.

Now in September the egrets are gone. The Monterey pine is dead and scheduled for removal soon.…

Now in September the egrets are gone. The Monterey pine is dead and scheduled for removal soon.…

The screenshot image

The screenshot image

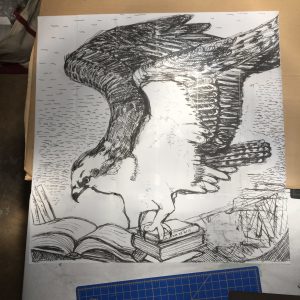

The drawing enlarged

The drawing enlarged

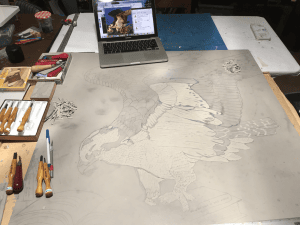

Computer screen and work in progress

Computer screen and work in progress