Oakland Zoo Celebrates Locals (in more ways that you think!)

by Leslie Storer

The Oakland Zoo has just opened California Trail, a series of habitats featuring species that are currently or were once found in California. This is a theme near and dear to my heart. My career path found me interpreting wild animals from around the world to zoo guests. The whole time I asked myself, ‘What about the species in our backyard?’

California Trail is home to black bears, brown bears, jaguars, mountain lions, bison, gray wolves, California condors, and bald eagles.

I am proud to be associated with this project as an animal care staff member, because of the emphasis on rescued individuals and the ties with conservation partners. There’s another reason I’m especially excited about this project, but that’s a surprise.

California Condor Program Information

California Condor Program Information

The California condor program is a prime example of the direction modern zoos are going. The two males in the condor habitat were hatched at other zoos and are members of the breeding population, which means they will live in Oakland until duty calls. What guests do not see (unless they are watching the webcam) are any condors that may be at our condor recovery center. We work with field biologists at Pinnacles National Monument and Ventana Wildlife Society in Big Sur who are monitoring wild individuals for lead poisoning. If the biologists discover an individual suffering from lead poisoning, the bird is transported to the Oakland Zoo where several staff members, myself included, are specially trained to handle and treat them. While guests marvel at the North America’s largest flying bird, they also learn about their conservation story: from 22 birds to over 400, more than half of whom are in the wild today.

Native Bird Information

Native Bird Information

Leslie Storer is a GGBA Board Member who started developing her passion for birds at the age of twelve as a volunteer at the San Francisco Zoo. She is currently an animal care manager at the Oakland Zoo, where she is part of the team of people specially trained to treat wild California condors for lead toxicity.

Raptors in our own backyard…

Raptors in our own backyard…

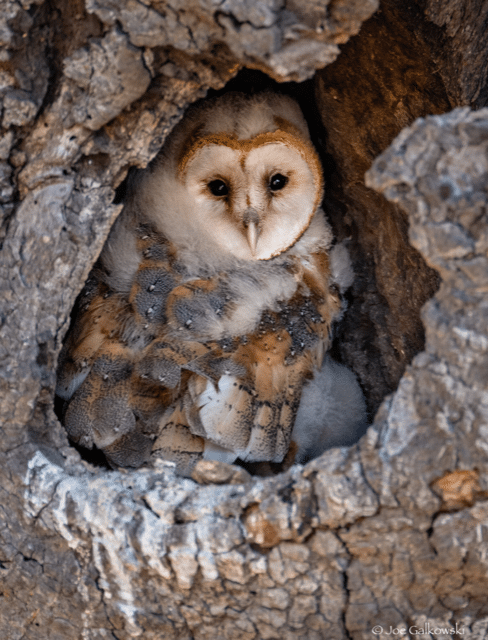

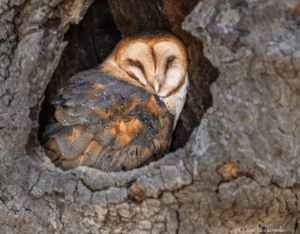

Female Barn Owl nesting in Oak cavity by Joe Galkowski.

Female Barn Owl nesting in Oak cavity by Joe Galkowski.

Barn Owl family by Joe Galkowski

Barn Owl family by Joe Galkowski

Owlets by Joe Galkowski

Owlets by Joe Galkowski

Birds of the Sierra class, by Noreen Weeden

Birds of the Sierra class, by Noreen Weeden

GGBA members outside the governor’s office.

GGBA members outside the governor’s office.

GGBA members meet with San Francisco Assembly member David Chiu,.

GGBA members meet with San Francisco Assembly member David Chiu,.

GGBA members meet with Mary Nicely (in red dress), chief of staff for East Bay Assembly member Tony Thurmond. Mary told us how she loves watching a Peregrine Falcon hunt outside the window of the district office in downtown Oakland!

GGBA members meet with Mary Nicely (in red dress), chief of staff for East Bay Assembly member Tony Thurmond. Mary told us how she loves watching a Peregrine Falcon hunt outside the window of the district office in downtown Oakland!

Brandt’s Cormorants photo by Bob Gunderson

Brandt’s Cormorants photo by Bob Gunderson