Wild Osprey Boat Cruise

By Melani King

Osprey boat tour? That was the email subject line from my friend Ann inquiring whether I’d be interested in this boat trip. Of course I would! What better way to check out many of the Osprey pairs from a bay vantage?

Disclaimer: I am one of the many Richmond and Rosie, sfbayospreys.org-obsessed viewers. And so is my retired husband. Before I leave for work, the webcam site is left up onscreen, full sized, so he can check on them throughout the day.

So as soon as I signed up, my husband piped in that he wanted to go too.

Monday morning we swung by to pick up Ann and another friend and drove the short distance from Pt. Richmond to the Marina Bay Yacht Harbor where we boarded Tideline’s boat for the 10:00 am Wild Osprey Cruise. The weather cooperated—calm waters, moderate air temperature, clear skies, and no wind.

Tony Brake provided background about the increase of nesting pairs within the past twenty years and showed us maps with successful and unsuccessful nest site locations. Ospreys will use quite a variety of structures, including relic cranes, utility poles, industrial light standards, as well as purpose-built platforms, along urban shorelines.

Photo of Osprey nest in lights by Melani King

Photo of Osprey nest in lights by Melani King

Appropriately, as it was Memorial Day, the first stop was to view the nest atop the Whirley Crane next to the Red Oak Victory ship. Rosie was in the nest with Richmond nearby on the cables.

As the boat passes by the shore of Brooks Island, a variety of birds can be seen on the sandy spit: Brown Pelicans, the largest known Caspian Tern colony, and Western Gulls.

Photo of Brook’s Island Caspian Terns by Melani King

Photo of Brook’s Island Caspian Terns by Melani King

Two ospreys were easily observed sitting in a nest built on a low platform just beyond Sandpiper Spit in Brickyard Cove. This was by far the closest we were able to see these magnificent birds without the aid of a webcam!

Moving north, along the way, other nests are visible with binoculars including one next to the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge that I see while driving to and from Marin. Passing under the bridge the boat takes us to more nests built atop lighting structures at the ends of piers coming from Pt. Molate. One nest, seemingly empty, reveals some movement—we see chicks. An osprey takes flight from an observation perch and flies to the nest.…

Photo of Horned Grebe by Bob Gunderson

Photo of Horned Grebe by Bob Gunderson

Photo of Black Phoebe by Bob Gunderson

Photo of Black Phoebe by Bob Gunderson

Photo of Steller’s Jay by Doug Mosher

Photo of Steller’s Jay by Doug Mosher

Hillary Powers works on her Clark’s Grebes / Photo by Cindy Margulis

Hillary Powers works on her Clark’s Grebes / Photo by Cindy Margulis

Richmond Chalk it Up Artists / Photo by Eleanor Briccetti

Richmond Chalk it Up Artists / Photo by Eleanor Briccetti

Parade of Brown Pelicans by Laurie Wigham / Photo by Cindy Margulis

Parade of Brown Pelicans by Laurie Wigham / Photo by Cindy Margulis

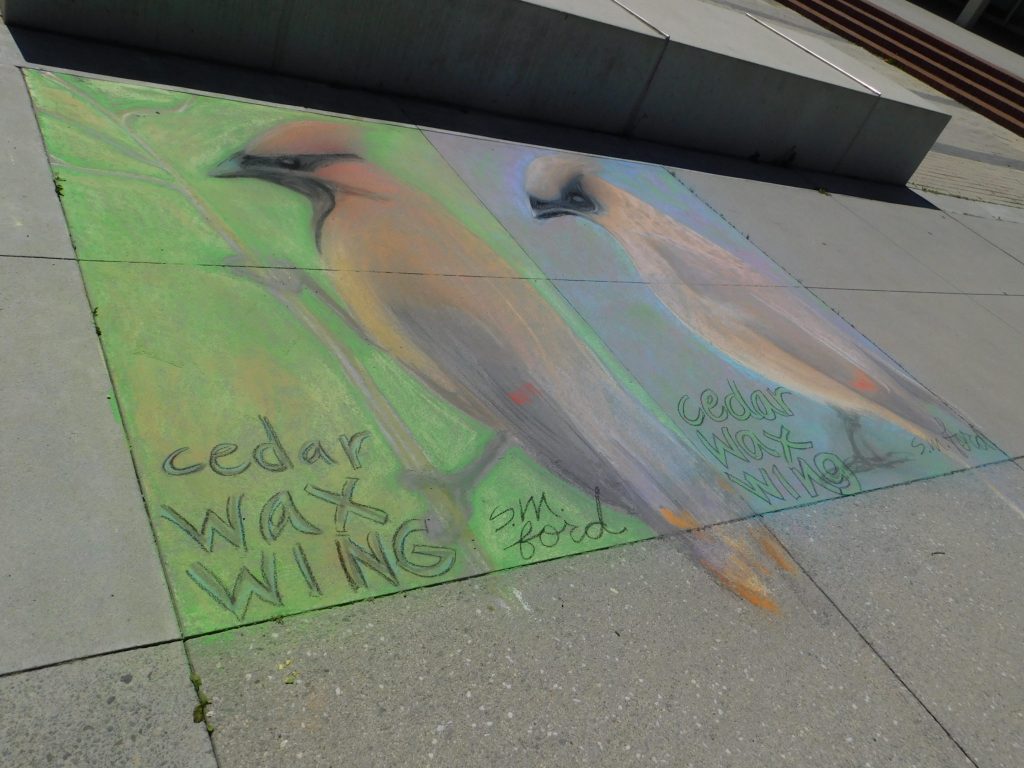

Susan Ford’s Cedar Waxwings / Photo by Cindy Margulis

Susan Ford’s Cedar Waxwings / Photo by Cindy Margulis

Cedar Waxwing by Rick Lewis

Cedar Waxwing by Rick Lewis