Burrowing Owl docents start their 11th season

By Della Dash

Everyone loves Burrowing Owls… once they actually see one.

As Burrowing Owl docents with Golden Gate Bird Alliance, we get the added thrill of helping people see their first owl and learn more about them. We’re monitoring owls, and creating owl allies!

GGBA will hold its annual training for Burrowing Owl docent volunteers this month, on Saturday, September 23. You’re invited to join us! (Details below.) But first, I’d like to share an update on our East Bay Burrowing Owl population.

Species of Special Concern

Once abundant throughout California, Burrowing Owls were a ubiquitous part of the Bay Area landscape. But as their habitat of open fields dwindled, so did their numbers. The Burrowing Owl is currently a federal and state “Species of Special Concern” and considered a likely candidate to be listed under the State of California’s Endangered Species Act.

Burrowing Owls are the only ground-dwelling owl in North America, and are typically the only owls likely to be seen roosting during daylight and hunting in the early morning and evening. Just 8-10 inches tall, they live in ground squirrel burrows or rocky outcroppings and hunt insects, rodents, and other small prey. They favor grasslands, open fields, and areas with low vegetation.

Burrowing Owl at Cesar Chavez Park by Mary Malec

Burrowing Owl at Cesar Chavez Park by Mary Malec

For the population to recover, Burrowing Owls need safe breeding, foraging, and over-wintering sites. Although historically there were ample breeding populations throughout the Bay Area, the area around the Bay has now become primarily an over-wintering site. “Our” owls have been documented at summer breeding spots as far away as Idaho.

Local over-wintering sites include Cesar Chavez Park in Berkeley, Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline in Oakland, Coyote Hills Regional Park in Fremont, Shoreline Park in Mountain View, and Santa Clara County, where Santa Clara Valley Audubon Society manages property that holds a breeding population.

GGBA Docent Program

The East Bay Shoreline Burrowing Owl Docent Program, co-sponsored by Golden Gate Bird Alliance and the City of Berkeley, is intended to make parks and open spaces more welcoming and safer places for over-wintering Burrowing Owls. GGBA docents invite all park visitors, with a special focus on dog walkers, to look through a viewing scope or binoculars to see the owl(s). We focus on three main messages:

1) Keep all dogs leashed, except in the designated off-leash areas.

2) Don’t allow dogs to approach the owls or chase any other wildlife in the park.…

American Robin at a bird bath by Bob Lewis

American Robin at a bird bath by Bob Lewis Greater Roadrunner panting, by Bob Lewis

Greater Roadrunner panting, by Bob Lewis White-throated Chat panting, by Bob Lewis

White-throated Chat panting, by Bob Lewis Spotted Eagle-Owl panting, by Bob Lewis

Spotted Eagle-Owl panting, by Bob Lewis

Lade Elliot Island from the air by Ian Morris

Lade Elliot Island from the air by Ian Morris Lady Elliot island and the Great Barrier Reef

Lady Elliot island and the Great Barrier Reef Brown Noddies on Lady Elliot island by Eric Schroeder

Brown Noddies on Lady Elliot island by Eric Schroeder Chestnut-Backed Chickadee eggs in nest box / Cellphone photo by Anthony DeCicco

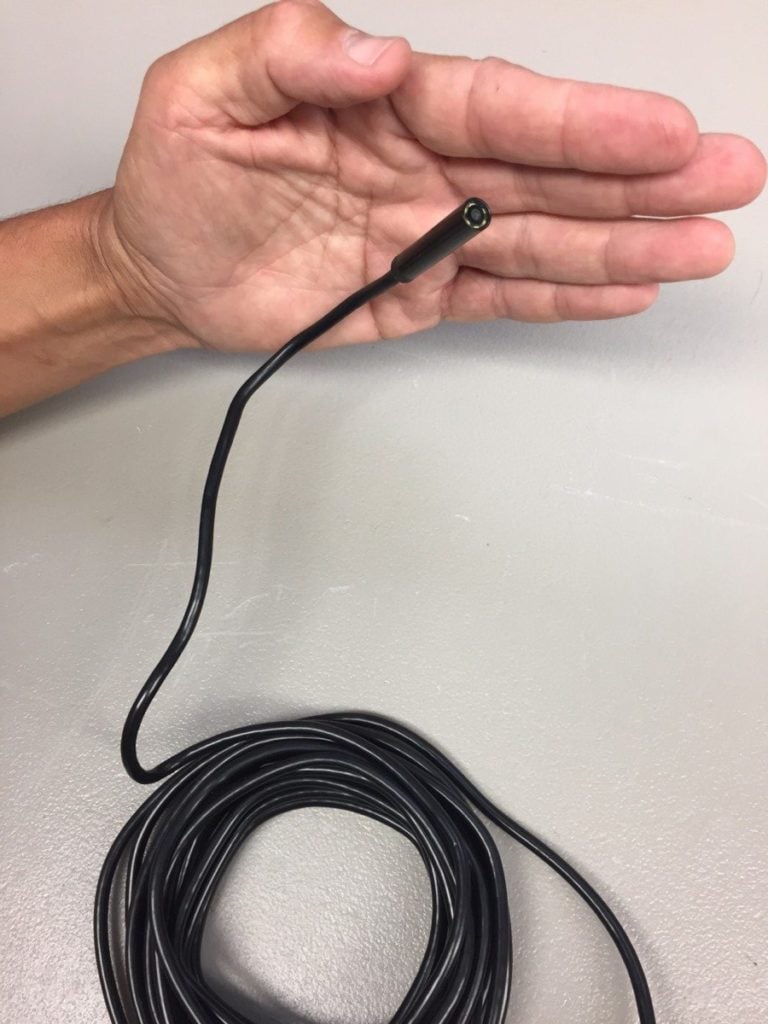

Chestnut-Backed Chickadee eggs in nest box / Cellphone photo by Anthony DeCicco This is one small camera! Photo by Ilana DeBare

This is one small camera! Photo by Ilana DeBare Eco-Ed students using the nest box camera / Photo by Anthony DeCicco

Eco-Ed students using the nest box camera / Photo by Anthony DeCicco Aerial view of Southeast Farallon Island

Aerial view of Southeast Farallon Island Common Murre adult (probably father) and chick at the Farallon Islands, by Glen Tepke

Common Murre adult (probably father) and chick at the Farallon Islands, by Glen Tepke Tufted Puffin at the Farallon Islands, by Glen Tepke

Tufted Puffin at the Farallon Islands, by Glen Tepke