Toyon berries and the birds that love them

Editor’s note: Here in the Bay Area, there are no Northern Cardinals perched on snow-laden holly bushes. Instead, for iconic winter holiday imagery, we have Cedar Waxwings feasting on bright red toyon berries! In this article, reprinted from Bay Nature magazine, Golden Gate Bird Alliance field trip leader Alan Kaplan explains the role of these brilliant red berries in the winter food chain.

By Alan Kaplan

Wintering birds in our area often depend on the fruits of native and exotic (ornamental) berry plants to sustain them. Three common fruit eaters are American Robin, Cedar Waxwing, and Hermit Thrush.

In the 1970s, ornithologist Stephen Bailey looked at how these birds use berries in winter and how they interact with each other. (He was a graduate student at U.C. Berkeley at the time.) He found that toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) was the most important source of berries for robins, thrushes and waxwings, though they also make use of other berry plants on the university’s campus, such as cotoneaster, privet, pyracantha, holly and juniper.

Low in protein and calories, berries offer limited nutritional value, especially to small birds who need to consume their body weight in food each day to survive the winter. For example, a bird would need to consume 3 ounces of (dried) toyon berries to get the same 331 calories that could be had with only 2 ounces of sunflower seeds. Nevertheless, if you’re a wild bird you take what you can get!

Cedar Waxwing with toyon berries by Evleen Anderson

Cedar Waxwing with toyon berries by Evleen Anderson

Bailey found that he could learn a lot about bird behavior by watching them tackle a berried bush. Each of the three species he studied — American Robin, Cedar Waxwing, and Hermit Thrush — had a different strategy of getting its fill. Each competed with the others and none could exclude the others altogether.

The large American Robin throws its weight around, dominating the other birds when defending a rich bush of berries against individual Hermit Thrushes or a small number of Cedar Waxwings. Cedar Waxwings, in turn, overwhelm the defense of robins with their large numbers, making up with flocking what they lack in fierceness.

Both the robins and waxwings prefer to perch and pluck at berries within reach, and spend about 16 minutes at a time doing that. Robins take five berries during that time, and cedar waxwings take three. A robin might eat its weight in berries in a day (about 3 ounces), filling and emptying its crop three times per hour.…

San Leandro Bay count team, dressed for the cold / Photo by Rick Lewis

San Leandro Bay count team, dressed for the cold / Photo by Rick Lewis American Kestrel at San Pablo Reservoir by Pamela Llewellyn

American Kestrel at San Pablo Reservoir by Pamela Llewellyn Red Fox on the golf course near San Leandro Bay by Rick Lewis

Red Fox on the golf course near San Leandro Bay by Rick Lewis Counting in the U.C. Botanical Garden / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Counting in the U.C. Botanical Garden / Photo by Ilana DeBare House Wren at Point Isabel by Alan Krakauer

House Wren at Point Isabel by Alan Krakauer One benefit of counting at Sequoyah Country Club is a ride on the golf carts / Photo by Pat Bacchetti

One benefit of counting at Sequoyah Country Club is a ride on the golf carts / Photo by Pat Bacchetti

The dead Burrowing Owl on a park bench

The dead Burrowing Owl on a park bench

The Burrowing Owl that was found dead over Thanksgiving weekend / Photo by Miya Lucas

The Burrowing Owl that was found dead over Thanksgiving weekend / Photo by Miya Lucas

The Burrowing Owl that was found dead over Thanksgiving weekend / Photo by Doug Donaldson

The Burrowing Owl that was found dead over Thanksgiving weekend / Photo by Doug Donaldson

Spare the Birds

Spare the Birds Page from Running Wild by GGBA member Elaine Bond Miller

Page from Running Wild by GGBA member Elaine Bond Miller

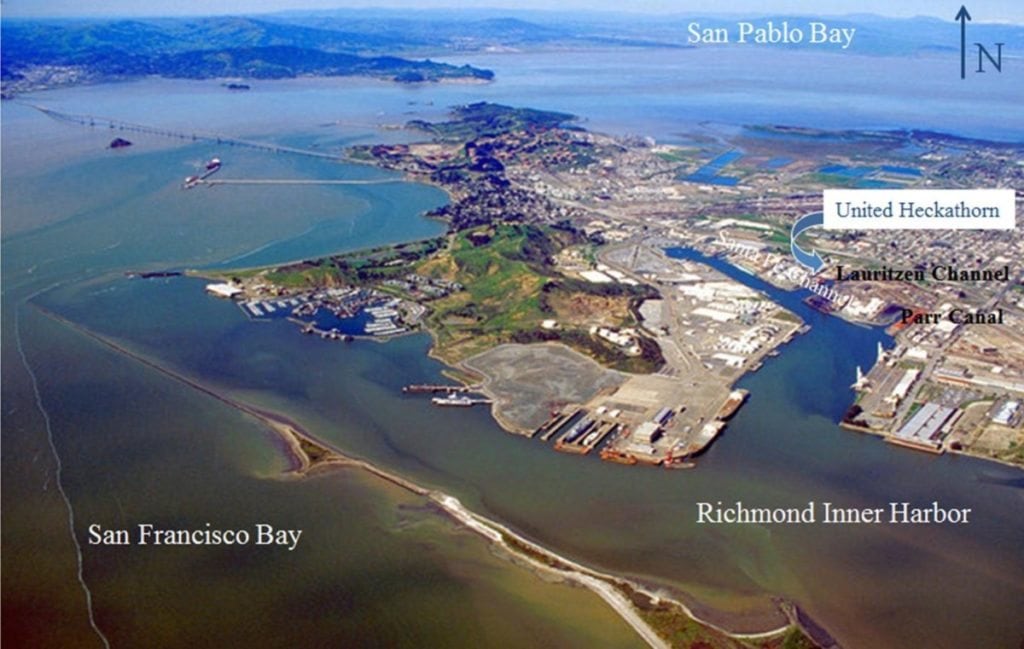

Aerial view of Richmond, showing the extensive waterfront.

Aerial view of Richmond, showing the extensive waterfront. Red-tailed Hawk at a window. Photo by Deborah Allen/National Wildlife Federation

Red-tailed Hawk at a window. Photo by Deborah Allen/National Wildlife Federation