Bay Birding Challenge Team: Stork Raven Mad

By Keith Maley (Stork Raven Mad Team Captain)

The day’s sunrise at 6:55 a.m. marked the start of the competition, and Team Stork Raven Mad was already gathered on Lake Merced’s concrete bridge filled with anticipation. Marsh Wrens rattled in the reeds. A Clark’s Grebe glided along the still water. A Sharp-shinned Hawk plucked its breakfast of an avian variety in the willow thickets. Male Great-tailed Grackles assembled a lek on the bridge to display in the cold, 45-degree air.

Great-tailed Grackle with visible breath – Rajan Rao

Great-tailed Grackle with visible breath – Rajan Rao

Observing an impressive number of species after 20 minutes at the bridge, the team piled into two cars and headed up to Fort Funston’s observation deck to see what we could over the ocean. Almost immediately, team member Rajan Rao spotted a continuing White-winged Scoter among the many Surf Scoters — a lifer for him! Not far away, a stunning Pacific Loon in alternate plumage preened on the water, affording great scope views for everyone. Two huge birds for the day, and it wasn’t even 8 a.m.!

At Lake Merced’s Harding Park Boat House, disappointment awaited. Failed attempts at a continuing Snow Goose, Northern Parula, and a Great Horned Owl seen sitting on a nest just the day before, were the first major letdowns for Team Stork Raven Mad. That is, until Lisa Bach shouted, “I SEE THE SNOW GOOSE!”– pointing to the end of the fishing dock where the bird stood nonchalantly. More shouting ensued, and we were off to our next destination, but not before Nina Bai picked up on a distant White-throated Swift among the swallows.

On to Ocean Beach for the continuing small flock of Black Scoters and a few lingering Brown Pelicans, which are mostly absent in the city this time of year. We raced to Battery Godfrey to see if there were any migrants moving. There were not. We did grab Wrentit, Spotted Towhee, Peregrine Falcon and a few other key species, but dipped on the long-continuing House Wren. Fort Scott yielded a wheeting Hooded Oriole from a palm tree as we stepped out of our cars. Swallows flew over the field, including a pair of Cliff Swallows. Five meadowlarks foraged in the grass.

Cutting across to El Polin Spring, we spent some time ticking additional species, including an Acorn Woodpecker, and the continuing Blue-gray Gnatcatcher that Dawn Lemoine and Lisa Bach located after some effort. Onto Crissy Field where no less than three breeding-plumaged Red-necked Grebes floated on the bay, and a late Say’s Phoebe hunted for flying insects in the dunes.…

Team East Bay Scrub Jays – Ilana DeBare

Team East Bay Scrub Jays – Ilana DeBare

Barn Swallow by Tara McIntire

Barn Swallow by Tara McIntire

While entanglements can be fatal for ospreys, fortunately the one trailing material here (lower left picture on the posterboard) was disentangled at the Port of Alameda nest by Craig Nikitas of Bay Raptor Rescue with the help of GGBA.

While entanglements can be fatal for ospreys, fortunately the one trailing material here (lower left picture on the posterboard) was disentangled at the Port of Alameda nest by Craig Nikitas of Bay Raptor Rescue with the help of GGBA.

Golden Gate Bird Alliance volunteers at the Meeker Slough cleanup – Janet Carpinelli

Golden Gate Bird Alliance volunteers at the Meeker Slough cleanup – Janet Carpinelli

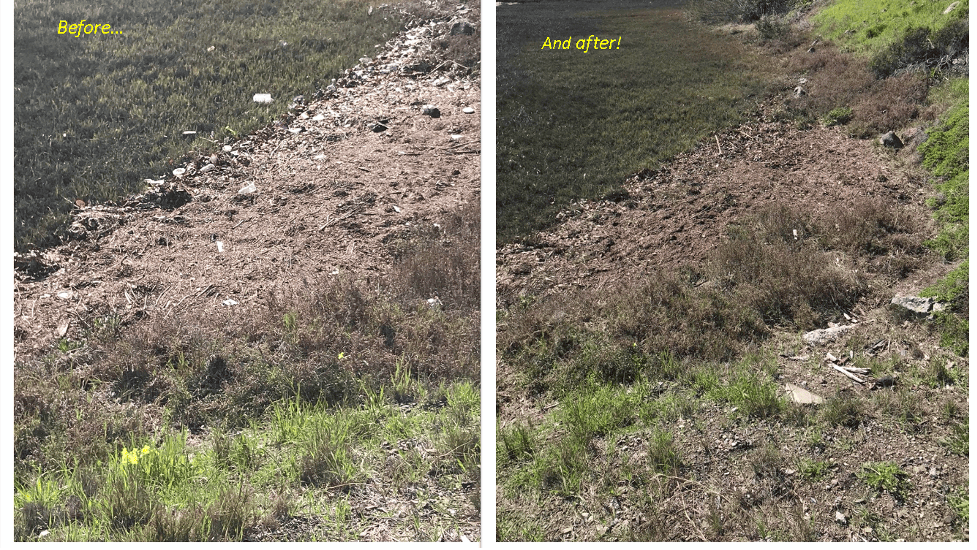

Before and After Meeker Slough Richmond Shoreline Cleanup

Before and After Meeker Slough Richmond Shoreline Cleanup

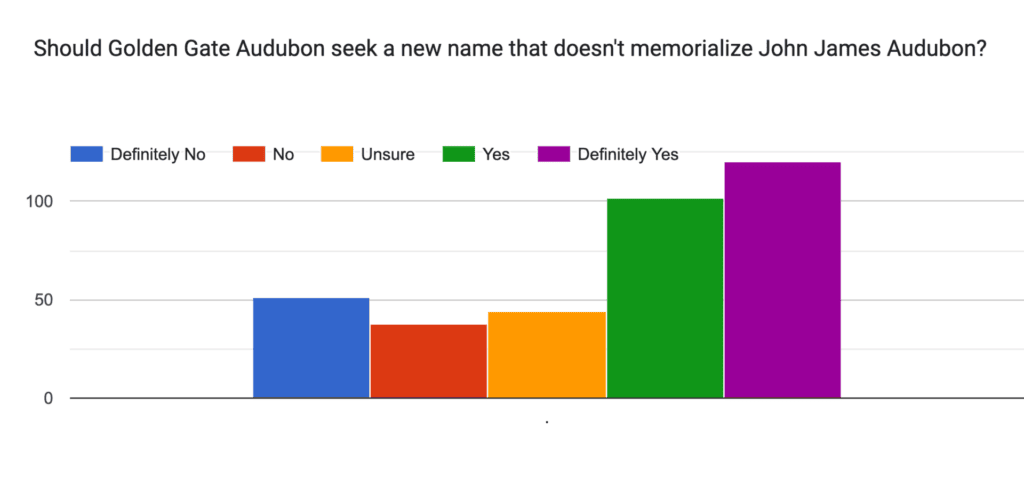

Results from the “Audubon” Name Change Preliminary Survey.

Results from the “Audubon” Name Change Preliminary Survey.

Hannah Breckel on an ecotour at Elkhorn Slough.

Hannah Breckel on an ecotour at Elkhorn Slough.