Corona Hill

By Dominik Mosur

The City of San Francisco is sprinkled with an array of small parks ideal for a birder on a time budget. One of my favorites, especially on a warm, east wind day in Fall, is Corona Hill.

Standing approximately 540 degrees above current sea level, Corona Hill is a lone outcrop on the northeast flank of the San Miguel Hills. It first appears in written history as the site of a brick factory at the turn of the 20th century. The brick makers used dynamite to rip the hill apart to extract the symmetrical layers of chert, a fine-grained sedimentary rock, that makes up much of the bedrock in this part of San Francisco. As the city rushed to develop the last remnant scraps of open space at the end of the 1940s, a parks superintendent named Josephine Randall envisioned a public destination on top of this hill. The result was a park and museum juxtaposed against the residential neighborhoods already sprawled over most of the other peaks of the growing city. Today 100,000 people visit Corona Heights Park and the Randall Museum each year.

Fall Migration

September through November, when the weather heats up, migrants move through the Central California Coast. Big numbers of Violet-green Swallows and Vaux’s Swifts and in some years Band-tailed Pigeons, Pine Siskins and other more irruptive species. Over twenty species of raptors have been noted passing the hill in the past 15 years. The bulk of these are turkey vultures, accipiters and red-tails but rarer species like kites, harriers, and kestrels pass over regularly when conditions are prime, as do the rarer migrating hawks like Broad-winged and Ferruginous Hawks, and more rarely Rough-legged and Swainson’s. Depending on the strength of the east winds the previous night, skeins of White-fronts or Cackling geese may pass over into midday as they redirect back to the valley. The hot east wind days can also blow in surprises like Lewis’s Woodpecker, Rock Wren and Townsend’s Solitaire.

As the seasons pass into winter, birding Corona Hill slows down considerably. Other than the occasional late migrant raptor or flock of misdirected water fowl, few new arrivals are noted after December until the early spring migrants begin their trek back north in March. However, Northern Saw-whet Owl and Burrowing Owl have both shown up in late Fall /early winter. Spring migration can be productive on days when many birds are moving through on the coast.…

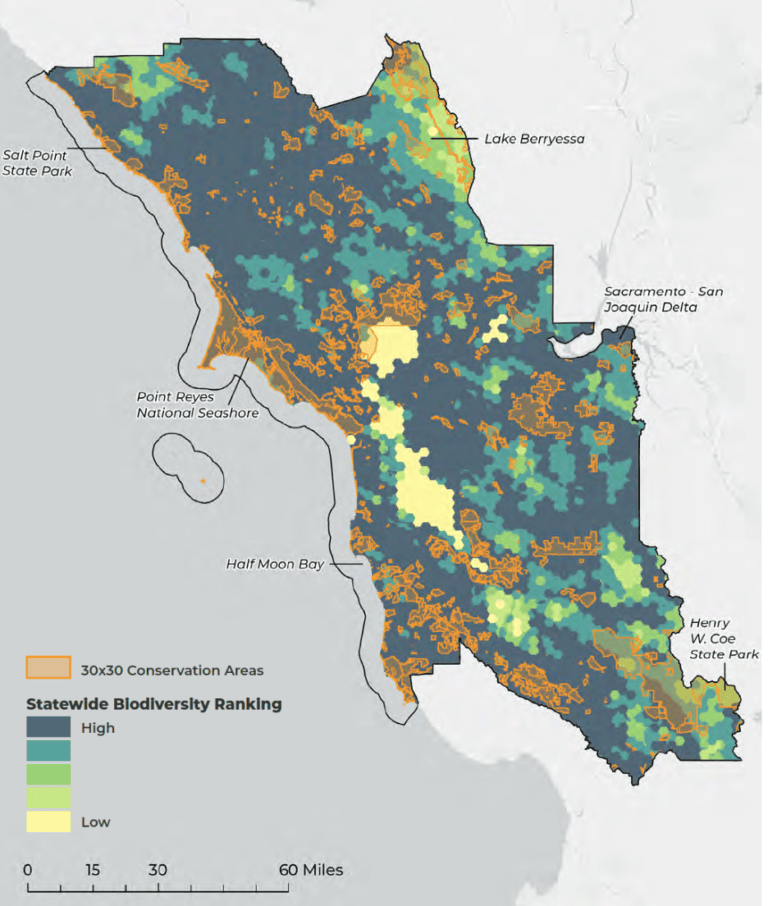

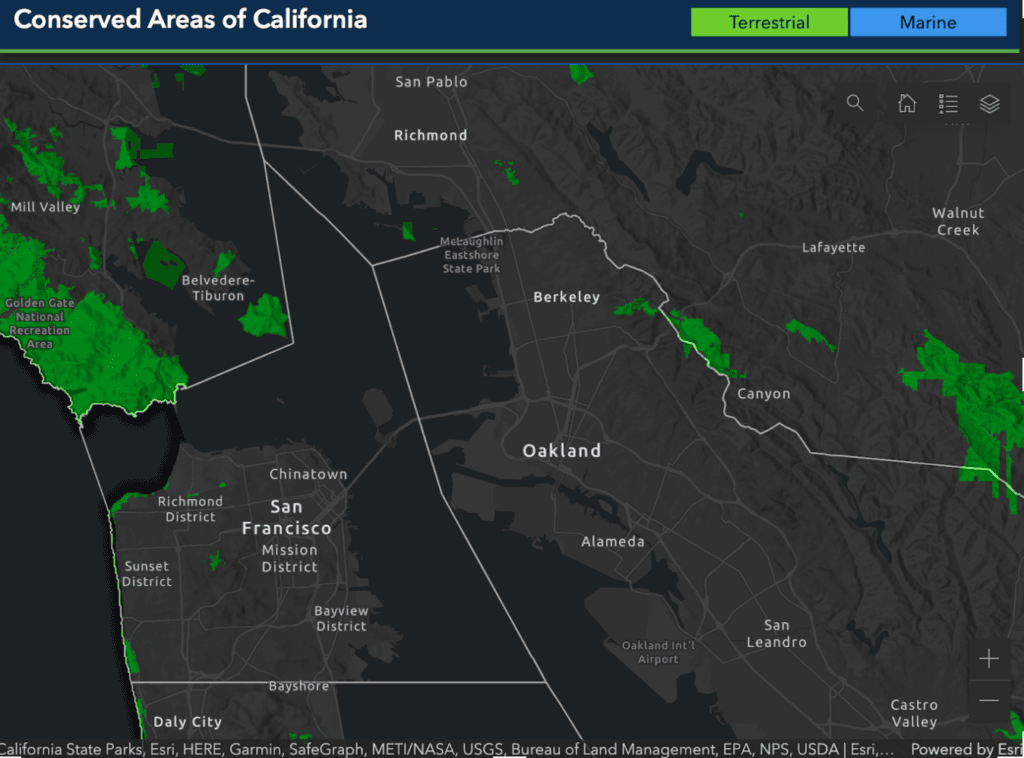

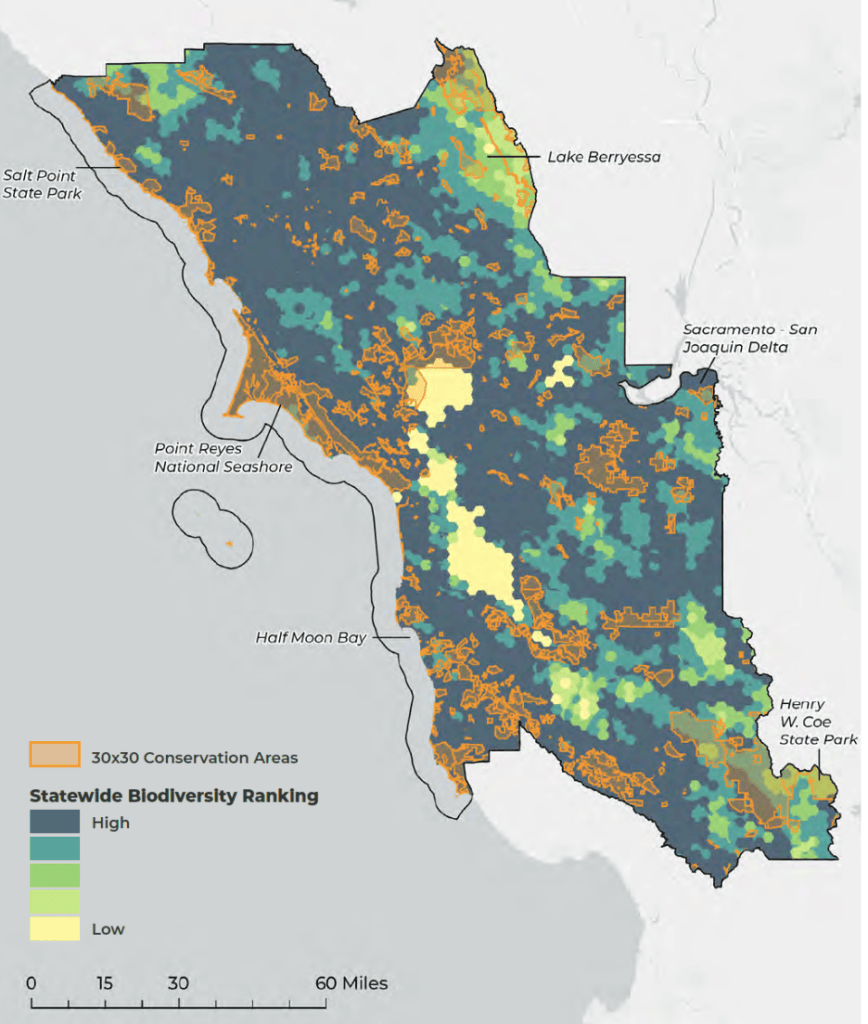

Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s terrestrial territory. Photo from 30×30 Conserved Areas Explorer

Golden Gate Bird Alliance’s terrestrial territory. Photo from 30×30 Conserved Areas Explorer

30×30 Appendix A

30×30 Appendix A

Male Pipeline Swallowtail, (note the gunmetal blue on hindwing) by Liam O’Brien

Male Pipeline Swallowtail, (note the gunmetal blue on hindwing) by Liam O’Brien

Female Greater Sage-Grouse, winner of the 2022 “Female Bird” category

Female Greater Sage-Grouse, winner of the 2022 “Female Bird” category

Pop-up blind in Greater Sage-Grouse country. Photo is from a different day and location

Pop-up blind in Greater Sage-Grouse country. Photo is from a different day and location