Honoring the Berkeley Bird Festival

By Ryan Nakano

Just over three week ago, Golden Gate Bird Alliance, in partnership with the California Institute of Community, Art and Nature, held the inaugural Berkeley Bird Festival, which I’m delighted to say was a great success.

Of course, success is subjective and dependent upon how we measure it. Since the festival ended, I’ve had more time to reflect on what exactly we were trying to accomplish. After several conversations with key organizers and participants I realized the festival’s success boiled down to its ability to answer a central question; how do we recognize birds?

In the context of birding, this is often a question about identification. In the context of the festival, recognition was more akin to honor. How do we honor birds? In what ways do we choose to acknowledge them for the beautiful creatures they are?

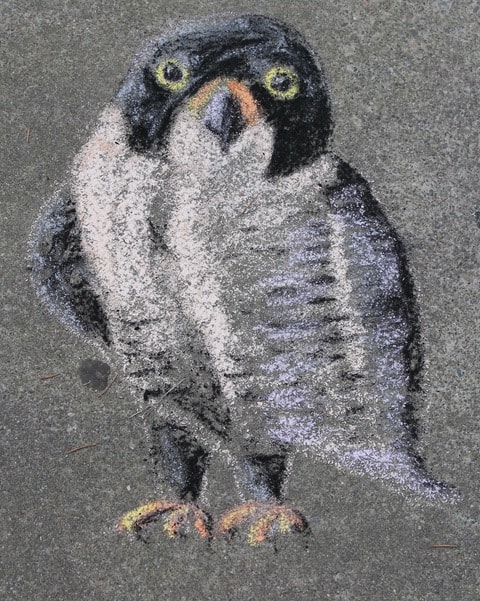

Eco-Ed Director Clay Anderson finishes his Peregrine Falcon chalk art at the Berkeley Bird Festival

Eco-Ed Director Clay Anderson finishes his Peregrine Falcon chalk art at the Berkeley Bird Festival

On the Saturday before the festival, our very own Clay Anderson, Director of Eco-Education, spent seven hours on the hard concrete semi-circle in front of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley. The next morning, he spent two more hours completing his chalk art masterpiece of a giant Peregrine Falcon, honoring the world’s fastest bird, and more specifically, the falcons known as Annie and Grinnell that nest on top of UC Berkeley’s historic Campanile.

Throughout the day others followed suit and took part in the practice of chalking out their favorite birds, not only outside of the MVZ, where a collection of bird specimens were on display, but also on the walkway near Li Ka Shing Center and at the entrance of Gather Kitchen Bar and Market.

U.C. Campus Birding Field Trip during the Berkeley Bird Festival by Dan Harris

U.C. Campus Birding Field Trip during the Berkeley Bird Festival by Dan Harris

Meanwhile, seven out of nine field trip groups set out in the early morning with scopes and binoculars to honor the diverse birdlife in Berkeley through the practice of birdwatching.

With over 200 people in total registered for these trips, each field trip filled to capacity and were generally well received by those in attendance.

“It was a really fun morning. I don’t think this trip was geared towards kids but the guy leading it was awesome and the group was really welcoming to both my 7 and 10 year old,” attendee Erik Dreher said of the UC Botanical Garden trip. “I remember we saw some rowdy flickers, a couple warblers and some sapsuckers.”…

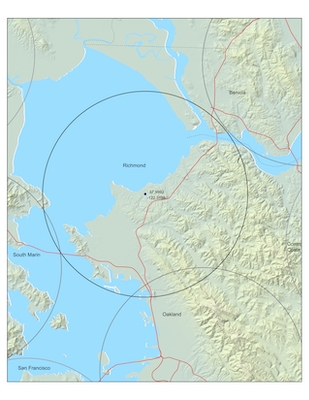

Ospreys, Rosie and Richmond spotted by the Golden Gate Bird Alliance Nest Cam on the Richmond shoreline.

Ospreys, Rosie and Richmond spotted by the Golden Gate Bird Alliance Nest Cam on the Richmond shoreline.

GGBA’s own Clay Anderson kicked the chalk art program off with a magnificent Peregrine Falcon, inspired by the falcon pair that nest on the UC Campanile.

GGBA’s own Clay Anderson kicked the chalk art program off with a magnificent Peregrine Falcon, inspired by the falcon pair that nest on the UC Campanile.

Red-tailed Hawk with a message: Don’t use rodenticides!

Red-tailed Hawk with a message: Don’t use rodenticides!

Bufflehead by GGBA board member Amy Chong. She managed to capture its iridescence!

Bufflehead by GGBA board member Amy Chong. She managed to capture its iridescence!

A “wild parrot of Telegraph Hill”

A “wild parrot of Telegraph Hill”

Peregrine Falcons were a popular subject!

Peregrine Falcons were a popular subject!

Grant Yang’s finished Lazuli Bunting

Grant Yang’s finished Lazuli Bunting

An Ivory-billed Woodpecker -— extinct in nature but alive on the UC sidewalk — by Brenda Helm

An Ivory-billed Woodpecker -— extinct in nature but alive on the UC sidewalk — by Brenda Helm

Nukupu’u, a Hawaiian honeycreeper that is most likely extinct, by Michael Helm

Nukupu’u, a Hawaiian honeycreeper that is most likely extinct, by Michael Helm

This young artist drew habitat as well as a bird

This young artist drew habitat as well as a bird

Bonaparte’s Gull chalk art

Bonaparte’s Gull chalk art

Peacock!

Peacock!

Pileated Woodpecker and chicks

Pileated Woodpecker and chicks

Native American-style Thunderbird

Native American-style Thunderbird

This artist depicted the evolution of birds from other dinosaurs

This artist depicted the evolution of birds from other dinosaurs

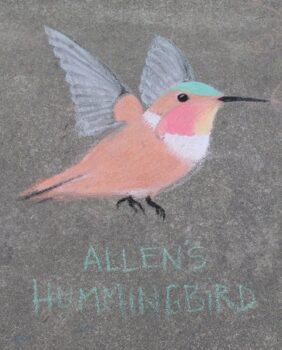

A much larger-than-life hummingbird

A much larger-than-life hummingbird

Painted Bunting

Painted Bunting

Artists spread out, making the whole walkway their canvas

Artists spread out, making the whole walkway their canvas

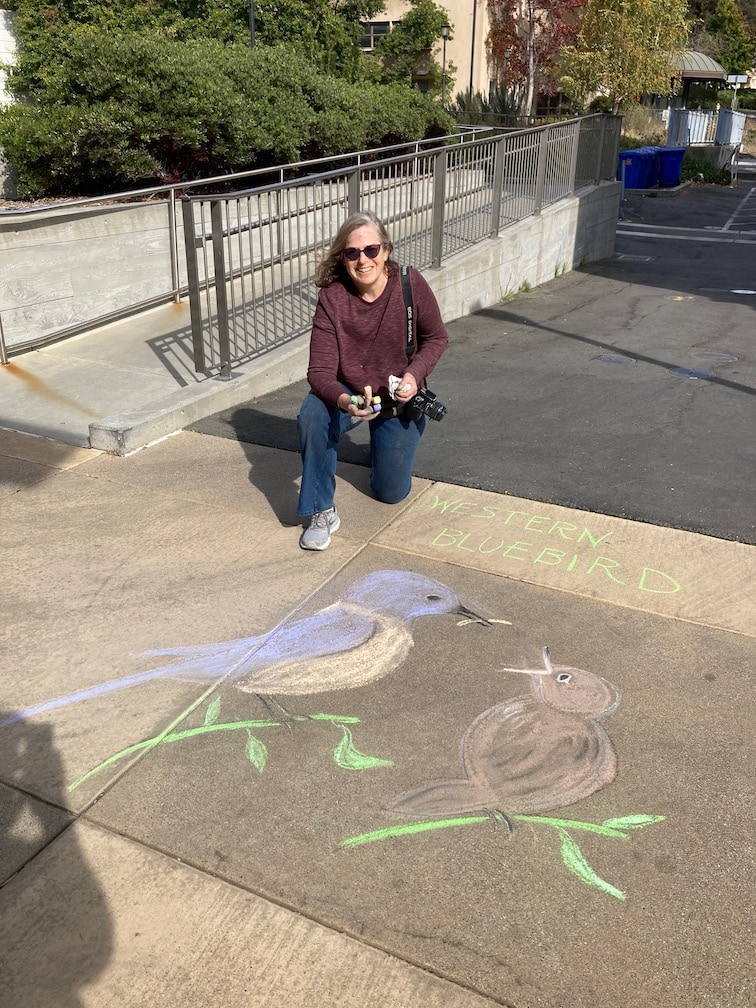

The author, one of those “me? I can’t draw” people, with her Western Bluebirds

The author, one of those “me? I can’t draw” people, with her Western Bluebirds

At the end of the day, time to clean up. Thank you, Clay and all the participants! There were many more beautiful chalk birds than we could fit in this blog post.

At the end of the day, time to clean up. Thank you, Clay and all the participants! There were many more beautiful chalk birds than we could fit in this blog post.

Allen’s Hummingbird feeding on Nicotiana sp. in the South American Area at UCBG by Melanie Hofmann

Allen’s Hummingbird feeding on Nicotiana sp. in the South American Area at UCBG by Melanie Hofmann

Burrowing Owl behind a fence

Burrowing Owl behind a fence