Birds for breakfast

By Alan Krakauer

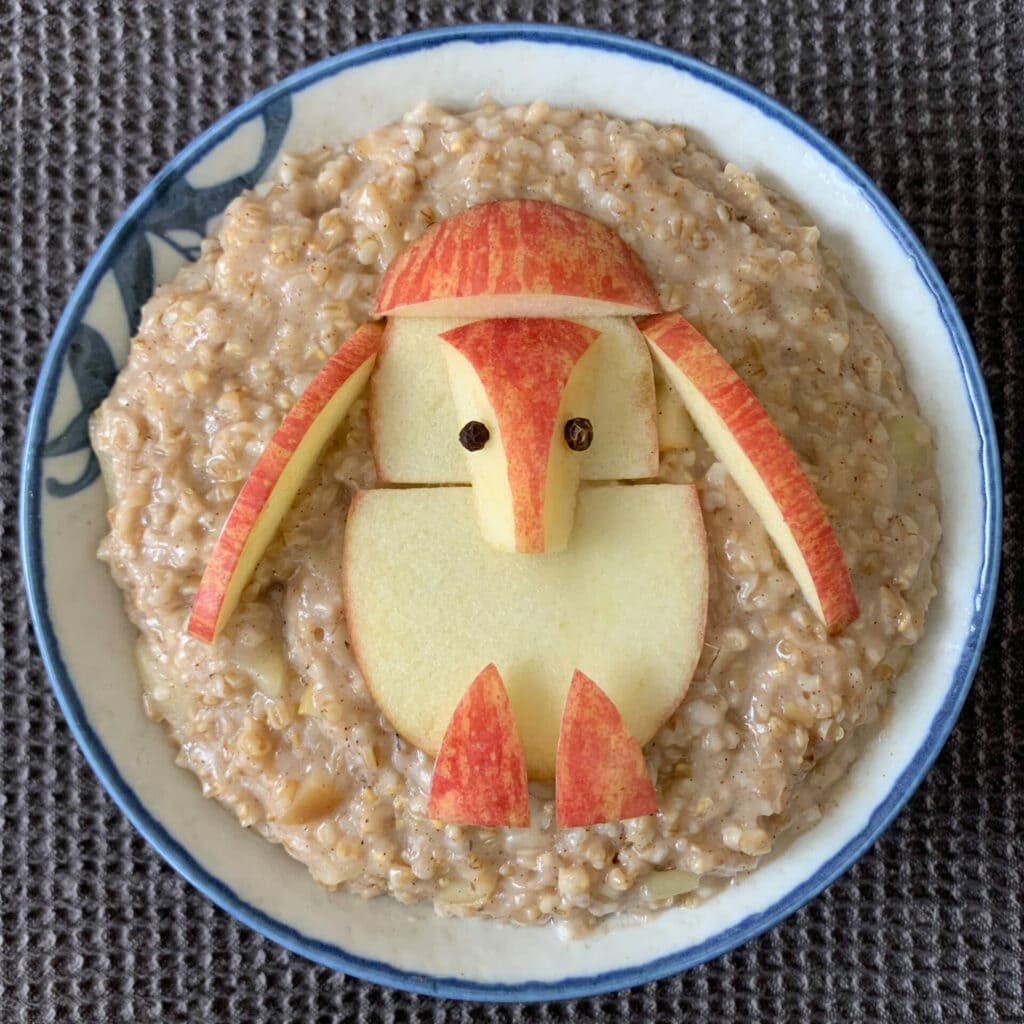

Breakfast cockatoo by Alan Krakauer

Breakfast cockatoo by Alan Krakauer

The past year of Covid-19 saw folks change how they relate to nature. Like many of you, my wife and I enjoyed a bit of a silver lining by getting reacquainted with our local wildlife. Attendance in nearby parks soared as people sought freedom and relief in the outdoors. When one can’t get outside to scratch this itch, sometimes biophilia can find a strange and creative outlet. For us, it changed how we have breakfast!

I present to you: Fruit Art!

When lockdown began last March, we decided to try eating healthier by making oatmeal every morning. Instead of just throwing some pieces of fruit into the pot, I started decorating the oats to lighten the mood as we grappled with the uncertainty of the pandemic.

Some of the inspiration came from my father-in-law: We’d laughed out loud at the whimsical mandarin, apple, and banana sections he arranged into faces for breakfast. I also channeled my inner Charley Harper to leverage the simple geometric shapes that a piece of fruit can yield in a few quick cuts. As I became more familiar with this organic ephemeral art medium, I took on the challenge to make animal-inspired designs. Naturally this included a lot of birds. Here’s a selection of our bird-related breakfast art from the past 14 months.

Northern Cardinal in the style of Charley Harper, by Alan Krakauer

Northern Cardinal in the style of Charley Harper, by Alan Krakauer

Some were local species.

Bewick’s Wren for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

Bewick’s Wren for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

Wild Turkey for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

Wild Turkey for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

California Quail by Alan Krakauer

California Quail by Alan Krakauer

Pileated (?) woodpecker by Alan Krakauer

Pileated (?) woodpecker by Alan Krakauer

Some were from farther afield.

Prairie chicken or Sharp-tailed Grouse by Alan Krakauer

Prairie chicken or Sharp-tailed Grouse by Alan Krakauer

Penguin, definitely in the style of Charley Harper, by Alan Krakauer

Penguin, definitely in the style of Charley Harper, by Alan Krakauer

Ostrich for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

Ostrich for breakfast by Alan Krakauer

How many ways can you make an owl?

Breakfast Barn Owl by Alan Krakauer

Breakfast Barn Owl by Alan Krakauer

Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

Another Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

Another Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

Yet another Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

Yet another Great Horned Owl by Alan Krakauer

A couple of bonus bowls.

A kiwi, obviously, by Alan Krakauer

A kiwi, obviously, by Alan Krakauer

“Birbs,” unknown species, by Alan Krakauer

“Birbs,” unknown species, by Alan Krakauer

Curious about our recipe? We use steel-cut oats and typically add apple (whatever isn’t needed for the design), ground cinnamon, and vanilla extract. Any other extra bits of fruit are chopped and added to the bottom of the bowls before we spoon in the cooked oats. Occasionally we add a splash of milk, but no extra salt, sugar, or butter.…

Sandhill Skipper butterfly by Liam O’Brien

Sandhill Skipper butterfly by Liam O’Brien

Woodland Skipper butterfly by Liam O’Brien

Woodland Skipper butterfly by Liam O’Brien

Mourning Doves by Sivaprasad R.L.

Mourning Doves by Sivaprasad R.L.

Ring Mountain, in one of Brandy’s Breeding Bird Atlas survey areas. She saw a Vesper Sparrow there in April and a Rufous-crowned Sparrow in May. / Photo by Brandy Deminna Ford

Ring Mountain, in one of Brandy’s Breeding Bird Atlas survey areas. She saw a Vesper Sparrow there in April and a Rufous-crowned Sparrow in May. / Photo by Brandy Deminna Ford

Briones Regional Park, a perfect example of a people-free nature immersion zone. Photo by Tara McIntire.

Briones Regional Park, a perfect example of a people-free nature immersion zone. Photo by Tara McIntire.

A green darner (Anax junius) zooming through the sky. Photo by Tara McIntire.

A green darner (Anax junius) zooming through the sky. Photo by Tara McIntire.

Variegated meadowhawk (Sympetrum corruptum) in the author’s yard.…

Variegated meadowhawk (Sympetrum corruptum) in the author’s yard.…