Rocky Mountain Birding

By Daryl Goldman

The fabulous Rocky Mountain Birding Package will open the GGBA’s 2025 Birdathon fundraising event. Bidding on this amazing trip will run from February 14 to February 25, at www.32auctions.com/GGBA2025kickoff The trip is set for June 20 to June 28 2025, so we’d like to give you time to make your plans now. The main Birdathon Auction will open in May and there are many other exciting birding adventures and art in store, so stay tuned for more information on those items. The auction officially opens Sunday, May 11 at 1pm.

Rocky Mountain National Park by Allie Peterson

Rocky Mountain National Park by Allie Peterson

Experience 9 days/8 nights of Rocky Mountain birding with NO logistical planning or stress! Four-star resort condos, airfare, ground transportation, birding itinerary… they’re all taken care of for you. Just pack your clothes and optics and show up.

Rocky Mountain National Park by Steve Hunter

Rocky Mountain National Park by Steve Hunter

Rocky Mountain National Park by Viviana Wolinsky

Rocky Mountain National Park by Viviana Wolinsky

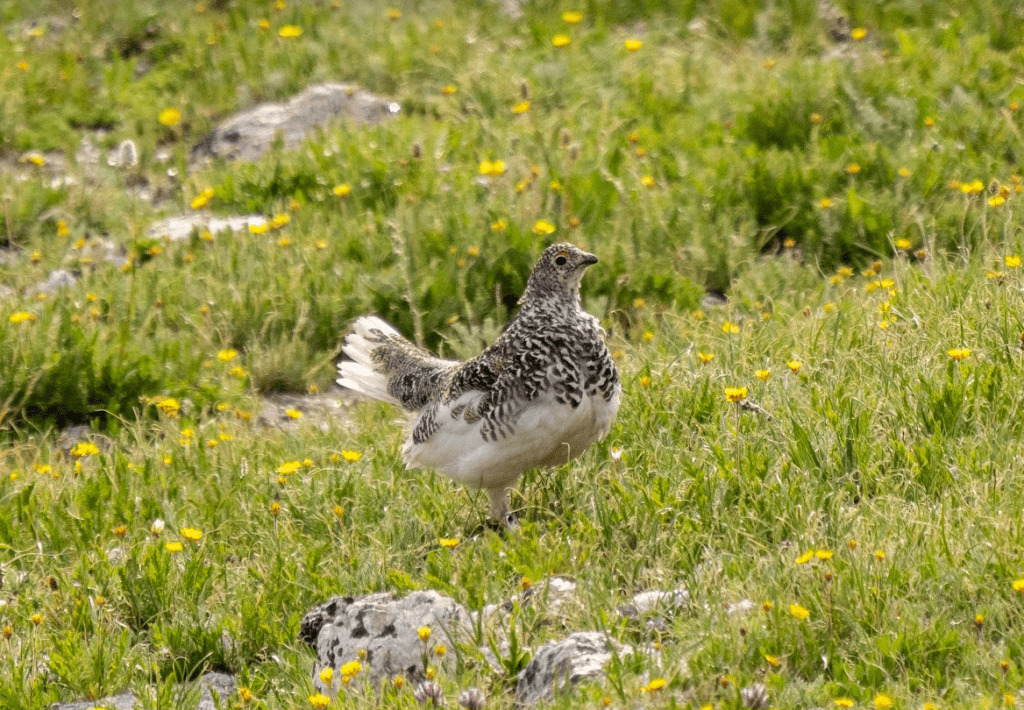

Join expert birders Viviana Wolinsky and Steve Hunter to explore the birds and sights of the amazing Rocky Mountains. Fly on Southwest from Oakland* to Denver and start birding as soon as you land. Spend your first night in an Estes Park lodge, rising early to search for White-tailed Ptarmigan in Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP). As a special treat, Sue Riffe, owner of Colorado-based She Flew Birding Tours and guide for the fabulous Grouse Extravaganza tour offered through GGBA Travel (and a woman with seemingly bionic hearing), will join us to bird the Rocky Mountain National Park portion of the trip. The trip through RMNP is incomparable and there is much to see along the road to your next stop in Steamboat Springs.

Dusky Grouse by Viviana Wolinsky

Dusky Grouse by Viviana Wolinsky

Spend 4 nights at the Steamboat Sheraton Resort Villas and then 3 nights at the Sheraton Mountain Vista Villas in the Avon/Vail Valley. After a bird-filled scenic drive back, you’ll fly out of Denver.

Avon/Vail Sheraton Vista Villas

Avon/Vail Sheraton Vista Villas

Steamboat Sheraton Resort Villas

Steamboat Sheraton Resort Villas

In addition to the White-tailed Ptarmigan, target birds include Dusky Grouse, Broad-tailed Hummingbird, Black-chinned Hummingbird, Williamson’s Sapsucker, Red-naped Sapsucker, Dickcissel, Gray Catbird, Eastern Kingbird, Canada Jay, Sand Hill Crane and many birds we just don’t see in the Bay Area.

Of course, you have the option of taking a birding break and using some of your free time enjoying the pools, hot tubs, golfing, biking, or the galleries and hot springs in Steamboat Springs.

You will share the two-bedroom condos with Steve and Viviana who will drive the rented SUV; meals are not included but there are many restaurant options and the opportunity to make meals at the condos.…

Jouanin’s Petrel found at Golden Gate Park and taken to Peninsula Humane Society for health reasons / photo provided by Peninsula Humane Society.

Jouanin’s Petrel found at Golden Gate Park and taken to Peninsula Humane Society for health reasons / photo provided by Peninsula Humane Society.

Bullock’s Oriole at Fort Mason by David Assmann

Bullock’s Oriole at Fort Mason by David Assmann

American Avocet/Glen Tepke

American Avocet/Glen Tepke

Nathan Staz/Unsplash

Nathan Staz/Unsplash

Phillip Strong/Unsplash

Phillip Strong/Unsplash