Oakland CBC: From Fog to UFO’s

By Ryan Nakano and Viviana Wolinsky

The fog is thick. The air, brisk. A small group of “early birders” strike out before the sun has time to show its face. It’s barely 5 a.m., and Dave Quady shines his flashlight after sensing a movement in the trees at the end of a side street near Claremont Canyon. At the edge of the beam, a Western Screech-Owl, the first bird seen and documented for this year’s Oakland Christmas Bird Count. Even before the Western Screech-Owl sighting, the group heard Great Horned Owls shortly after 4 a.m., softly calling as the birders emptied out of their vehicles near signpost 28.

“We listened to them for a while and went a bit further down Claremont Avenue, not wishing to attract smaller owls into the bigger owls’ neighborhood because they might be preyed upon,” Quady reminisced. “That’s when I saw the Western Screech-Owl and it was very, very satisfying.”

Fog amongst the trees at Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve on the day of the Oakland CBC by Patrick Coughlin

Fog amongst the trees at Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve on the day of the Oakland CBC by Patrick Coughlin

The day, as early and as gloomy as it was, was off to a great start.

As time went on, the sun eventually broke through the fog and more and more groups of birders gathered and dispersed, splitting off into smaller groups to cover 30 areas within the 15-mile diameter Oakland count circle. Two-hundred and sixty participants organized into teams via the impassioned work of Oakland CBC co-compilers Viviana Wolinsky and Dawn Lemoine. Eighty-seven of these birders were participating in the Oakland CBC for the very first time and 44 participants were beginning birders [or quite new to birding].

Utilizing eBird, the online tool that tracks bird sightings worldwide, for the first time in the Oakland CBC history as the main form of documentation, the groups submitted their bird observations tallying a preliminary number of 184 different species seen on December 19, 2021.

Black Turnstone at Albany Bulb on Oakland CBC by Alan Krakauer

Black Turnstone at Albany Bulb on Oakland CBC by Alan Krakauer

Out of all these species, one was designated the “Best Bird” of the count. Its claim to fame rests primarily on its very first sighting on the day of the Oakland count, a count with records that date back to 1938.

Seen by the Emeryville Crescent group, over 45 Black Skimmers, tern-like birds with strikingly large red and black underbite bills, were spotted at Radio Beach area with peeps, ducks, gulls, and terns.…

Rosie returns to the nest by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Rosie returns to the nest by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Rosie and Richmond on the nest by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Rosie and Richmond on the nest by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Rosie and Richmond coincubate eggs by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Rosie and Richmond coincubate eggs by SF Bay Osprey Cam

Acorn Woodpecker in the “bird species paint chip” project Field Guide.

Acorn Woodpecker in the “bird species paint chip” project Field Guide.

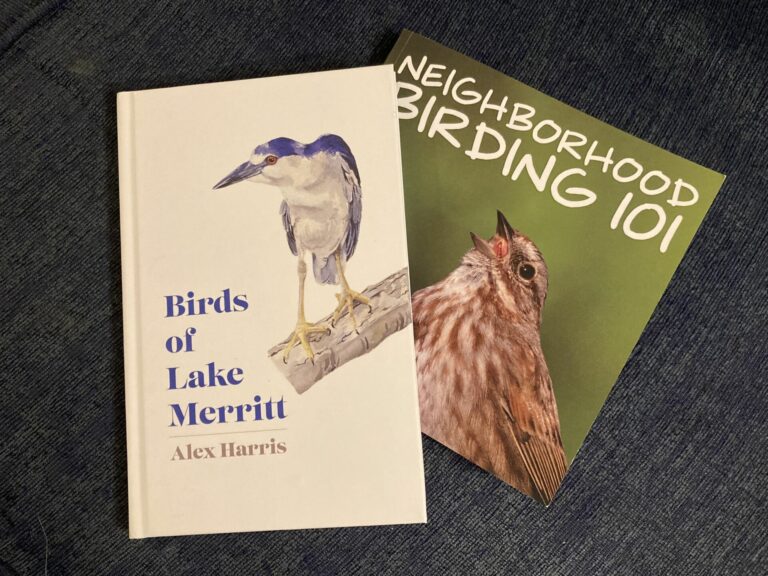

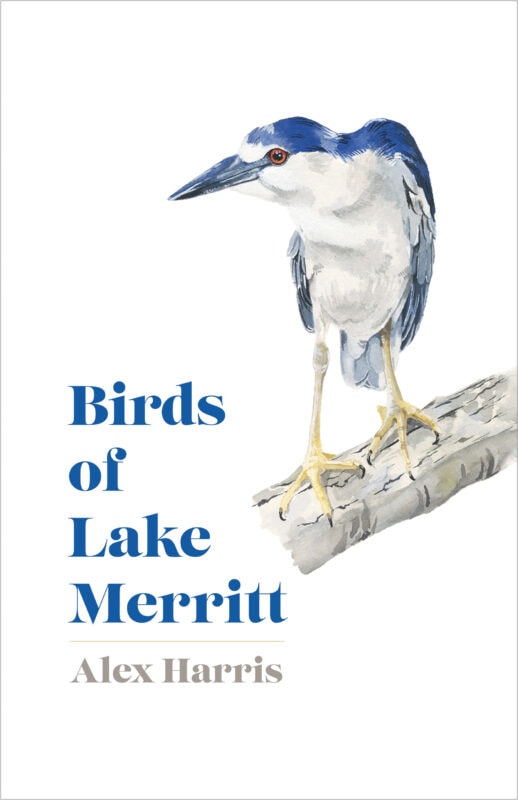

Birds of Lake Merritt by Alex Harris

Birds of Lake Merritt by Alex Harris

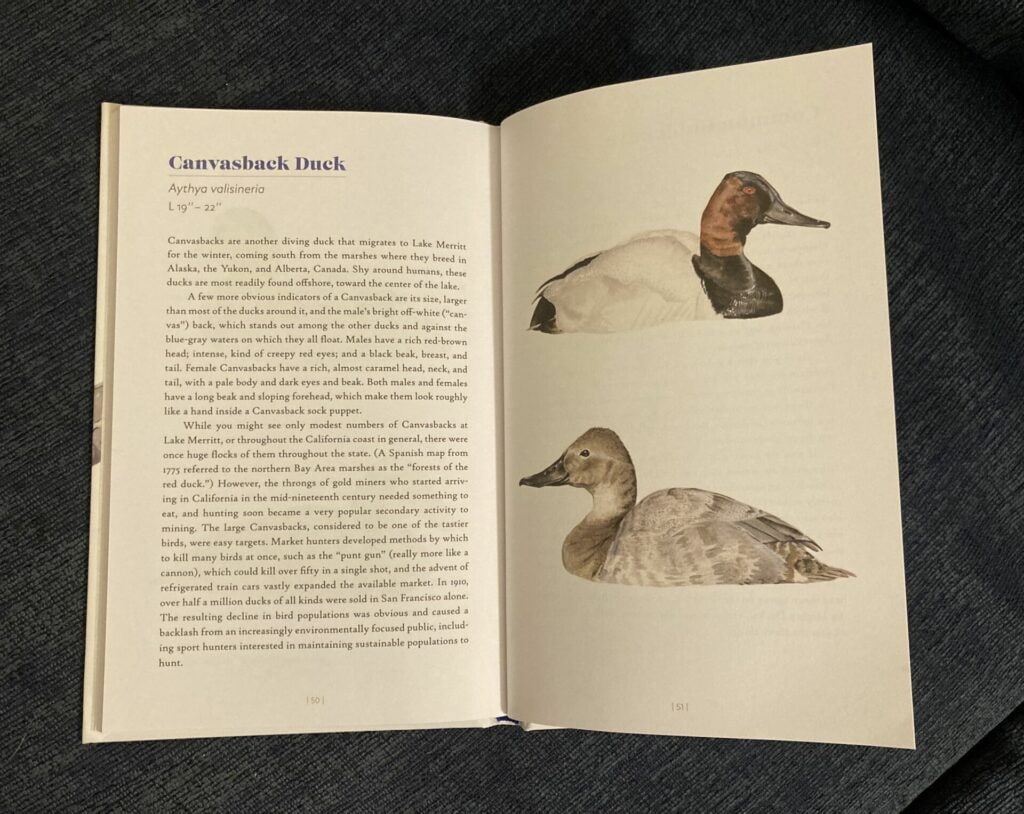

Canvasback page from Birds of Lake Merritt

Canvasback page from Birds of Lake Merritt

Swifts at McNear Brickyard in September by Michael Helm

Swifts at McNear Brickyard in September by Michael Helm