Sharing birds with tomorrow’s outdoor educators

By Analicia Hawkins and Aryn Maitland

Throughout the past year, opportunities to connect with the birding community in person and enjoy nature together have been few and far between. Even though birding alone can be a fulfilling experience, there’s something special about being able to share that experience with others—especially with people who may be birding for the first time.

Earlier this year, Golden Gate Bird Alliance members and staff led a day of birding and exploration for a group of young outdoor educators—an all-womxn cohort from the Outdoor Educators Institute (OEI), a program of Youth Outside.

OEI is a year-long program that supports young adults by providing immersive and culturally relevant training, development, and leadership opportunities. The program is designed to support participants in advancing their careers as educators in a way that centers under-represented groups working in the industry through inclusion and representation. As queer birders who rarely see other queer birders in a structured setting, it filled us with joy and hope to be in the company of such bright, passionate, and engaged birders, many of whom shared similar identities and experiences.

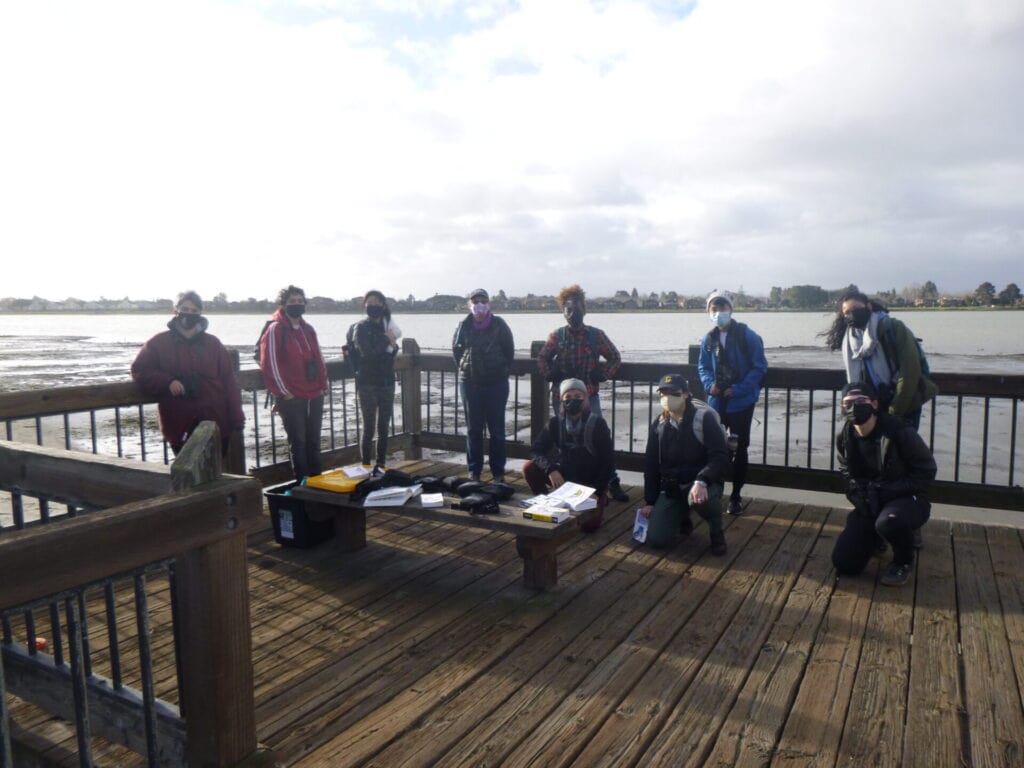

Outdoor Educators Institute participants and Golden Gate Bird Alliance volunteers at Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary / Photo by Dan Roth

Outdoor Educators Institute participants and Golden Gate Bird Alliance volunteers at Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary / Photo by Dan Roth

Members of the GGBA Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion committee planned a day-long excursion that led participants through two local wetland bird habitats. We began our day at the Elsie Roemer Bird Sanctuary in Alameda as the tide began to retreat, offering us excellent glimpses of various plover species, American Coots, terns, and more! Participants gathered on the viewing platform and, with the support of GGBA members, gained basic comfort and familiarity using binoculars—some for the very first time—and learned how to use various field guides. The enthusiasm from the group was infectious (COVID pun only slightly intended).

Afterward, we made the short drive to Arrowhead Marsh at MLK Jr. Regional Shoreline in Oakland. As we began our walk, members of the group stopped to appreciate an Anna’s Hummingbird perched on a fence showing off the striking colors of its gorget in the sun.

“I would have just thought that was just a regular bird on a fence if I were walking by, but it’s actually beautiful!” one of the participants remarked.

Anna’s Hummingbird By Bob Gunderson

Anna’s Hummingbird By Bob Gunderson

Outdoor Educators Institute participants at Arrowhead Marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare

Outdoor Educators Institute participants at Arrowhead Marsh / Photo by Ilana DeBare

A few steps later we looked up just in time to see a Northern Harrier gliding above the marsh, even pausing for a moment.…

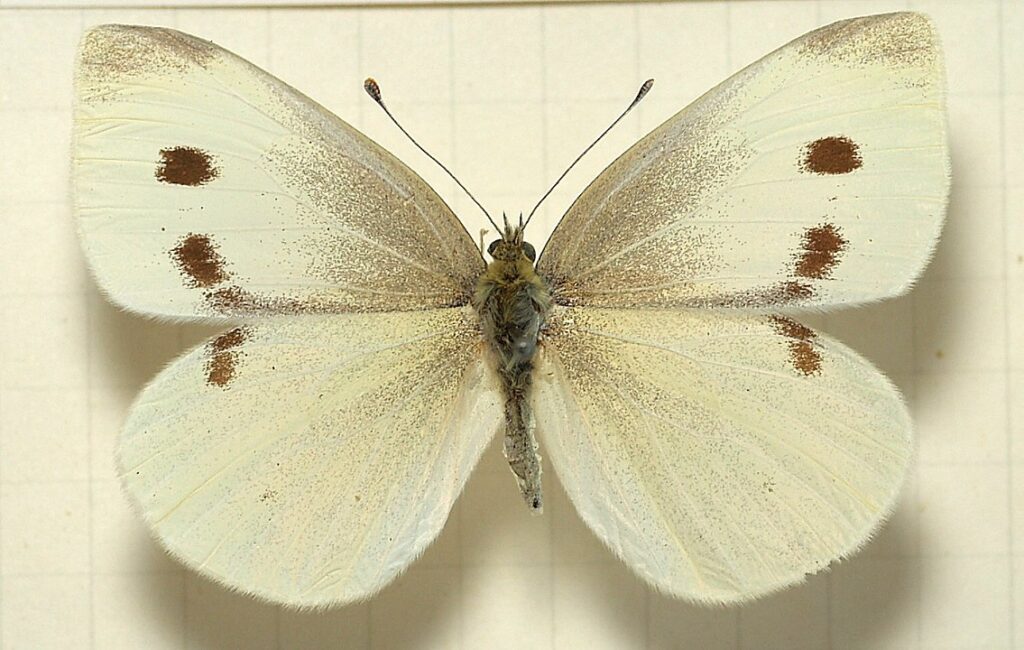

Cabbage White butterfly / Wikipedia

Cabbage White butterfly / Wikipedia

Brown Creeper by Bob Lewis

Brown Creeper by Bob Lewis

Native wildflowers in the Rotary Meadow on Mount Sutro, by Ildiko Polony

Native wildflowers in the Rotary Meadow on Mount Sutro, by Ildiko Polony

Sutro Stewards volunteers planting at Rotary Meadow, by Kelly Dodge

Sutro Stewards volunteers planting at Rotary Meadow, by Kelly Dodge

Rachel Lawrence and Alex Henry. Photo by Michael Stevens

Rachel Lawrence and Alex Henry. Photo by Michael Stevens

Rosie on the Whirley Crane last year, in March 2020

Rosie on the Whirley Crane last year, in March 2020

Rosie (left) and Richmond, together again, on March 4, 2021. You can identify Rosie by her speckled “necklace.”

Rosie (left) and Richmond, together again, on March 4, 2021. You can identify Rosie by her speckled “necklace.”

Richmond with his wings up and Rosie on the cable, March 13, 2021

Richmond with his wings up and Rosie on the cable, March 13, 2021